10 years after "Growth Hacking"

What's changed and what's new

More than a decade (!!) ago, I wrote Growth Hacker is the VP of Marketing predicting that traditional marketing teams were soon to be disrupted. In particular, I made several provocative points:

In the future, Marketing will require technical proficiency and less touchy feely skills

Tech products are ~trivial to build, and distribution will get harder than ever

New “superplatforms” are giving startups access to 100s of millions of users, raising the stakes for all

Hooking into APIs and integrating into new platforms are the domain of technical distribution-minded teams, not in the world of traditional marketing — which I defined as brand/comms/PR/etc

This was all published under a cheeky phrase that went right after the “VP Marketing” causing much chaos and FOMO that spread the post far and wide within the tech industry. (As designed 😜).

Soon after, the age of growth hacking emerged, with many changes happening in the industry. Many new job titles appeared — such as “Head of Growth” jobs, entire Growth teams forming within consumer + SaaS startups, and a blizzard of new terminology (NURR CURR RURR!? k-factor? D1/7/28!?), and much more.

Since then, 10 years have passed. How are we doing?

From abundance to scarcity

A decade ago, product growth was in a period of abundance. The iPhone launched, followed by the App Store, and people were excited about installing new apps. After all, you were competing against waiting in line and sitting quietly on the toilet. They’d actually check the App Store to see what had launched each day, and go look at the leaderboard — thus “trending” in the top apps was a big deal. They’d click on ads, curious about new experiences, and actually sign up and convert. In parallel, a decade ago Web 2.0 was in full swing. New social apps often got people to invite their friends. A developer could use email contact scrapers to juice the invites, deliverability was high, as were acceptance rates. New products were launched at major conferences like SXSW or on media publications like Techcrunch (before both rode into the sunset, from a relevance perspective). Channels that had been around for ages, like SEO, SEM, and email, were still relevant. Abundance.

Then the music stopped.

In 2024, things have narrowed quite a bit. Scarcity has replaced abundance, as we are on the closing years of the mobile S-curve. The novelty drive has decayed, and it’s now very low on mobile — people aren’t interested to try new apps, as their homescreens (and brains) are full of apps developed over the past decade. Instead of competing with waiting in line, developers now compete with a killer lineup of the most engaging/addictive apps ever — from messaging to short form video to 24/7 email.

The consumer novelty drive is important because it causes all sorts of goodness:

More organic growth / word of mouth and signup conversion

… but more one-and-done usage, comparison shopping, and higher churn

This base rate of new growth is stagnant on mobile, and that causes all sorts of problems that even sophisticated growth teams aren’t able to manage.

There are many limitations to growth hacking

The old hands who used growth hacking techniques on many products across many growth channels eventually found major limitations:

For startups, it turns out you can’t A/B test your way to product/market fit. You don’t have enough users to generate statistically significant data, and the changes you need to make in your product are often big, not small. Make big, bold moves, not little landing page changes — the latter won’t help you enough

While growth teams often delivery a steady stream of +5% lifts across a lifecycle, they can’t fight against the larger waves of seasonality, poor retention, S-curve dynamics, nor are they sometimes as impactful as doing dumb/simple things like doubling the customer acquisition budget or dropping the price. And sometimes you just need a big product swing to reset things

Growth projects work best when there’s a lot of data to quickly hit statistical significance, the metrics can be evaluated daily or weekly, and it affects an obvious thing like Revenue or Signups. This means they are best for top-of-funnel initiatives at large/scaled products, not startups and not longer-term factors like retention — thus limiting their use case

Aggressive growth projects often lead to UX cruft, slowly degrading long-term user engagement and retention. Yes, you can move short-term metrics by throwing a blocking modal that up-sells a subscription (yes newspaper websites, I’m talking about you!) but how long before that alienates long-term users?

In larger companies, the product teams often end up fighting with growth teams as they are often implemented as two separate squads of PMs/engineers/designers who overlap. The growth teams often get the reputation as hacky/bad who don’t stretch beyond technically simple projects

I could go on.

The point is, when these tools were tried in every conceivable situation and scenario, we found them to be helpful in some cases and not in others. For me, it was disappointing to see that startups found limited utility from using A/B testing throughout their product cycles.

I originally had hoped to find a new scientific process to finding product/market fit but in the end mostly found new tools/processes that mostly helped big products get even bigger. Early on it was theorized that you could, for instance, test many variations of landing pages to figure out a value prop before actually building the product. And then building very small products that could then be A/B tested at high iteration speeds to nail product/market fit. Instead A/B testing was mostly helpful for user acquisition and testing top-of-funnel UX but didn’t do much for figuring out long-term retention.

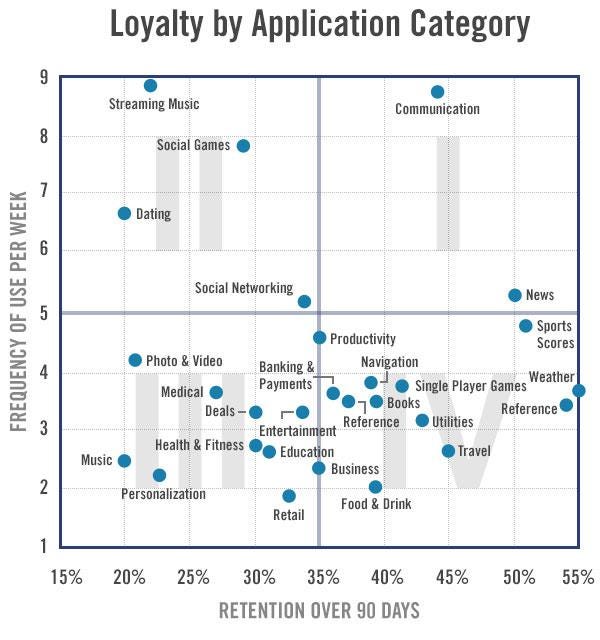

It would be several years before I was able to articulate **why** this was the case, in my essay on Nature vs Nurture — showing that sometimes you have high-frequency or low-retention in your usage patterns simply because of the product category you initially pick. Here’s a good chart to reference:

Imagine if you are a gaming app (in the top-left quadrant above). If you have poor retention but high frequency, how much can you A/B test yourself out of that quadrant. Over the years, I’ve come to believe that you can move things around a little bit, but not much. In fact it’s really the big decisions on product strategy — on what category you pick, what customer segment you choose — that determine your core product/market fit stats. And you can’t growth hack your way out of that.

Distribution/metrics culture won over Product Management (and everything else)

Despite the aforementioned limitations, this mindset around metrics-oriented distribution ultimately succeeded across larger products and teams, something I had not initially expected. Product Managers are simply expected to understand A/B testing and distribution metrics like CAC, LTV, D30, and other jargon. You interview for this. Companies have teams focusing on the New User Experience, and teams that help the Marketing groups with their landing pages and adtech APIs, but often none of these are called growth teams.

The language also evolved and expanded. Today, a very large % of marketers are called “growth marketers” and even a Head of Sales in a B2B context might describe themselves as a Head of Growth. At its peak, we saw Coca Cola appoint a Chief Growth Officer, a title that began to show up here and there beyond the tech industry.

Rather than get disrupted by the growth discipline, as I had predicted, instead we saw the other functional disciplines absorb it.

The ideas, jargon, and titles permeated the industry. While this helped many companies, it also commoditized the techniques. After all, I’ve written often of the Law of Shitty Clickthroughs, in which the performance of every growth channel decays over time because consumers become acclimated to different tactics (like getting invited to an app!) and tire of it. When many teams have the same ideas and employ the same tactics on the same channels, they burn out the collective customer psyche.

Where growth goes next

Today, there are still interesting opportunities and the fundamentals of growth strategy exist. After all, let me revisit the two of the bullets of the opening paragraph:

Tech products are ~trivial to build, and distribution will get harder than ever

New “superplatforms” are giving startups access to 100s of millions of users, raising the stakes for all

This is true, even more so than before. Generative AI will give us an incredible amount of leverage to build new apps simply by prompting and no code tooling. Platforms are even bigger than before, and new memes/apps/conversations spread instantly across billions of people.

In other words, there is a reinvention of growth channels, but today’s most effective tactics are very different than what existed before. While we are unlikely to install new apps, we are willing to follow new creators, or share videos/links/photos. We spend a ton of time on social media, within video apps, and comms/collab products in the workplace. It’s partly why creators, short-form video, and shareable memes have become such important growth drivers for new startups today, even though sometimes the spikes are short and ephemeral. And within the workplace, why PLG and bottoms-up growth are often fueled as much from co-workers sharing content as much as observing content posted by AI influencers.

This naturally leads to a new generation of “video-native” products that automatically generate content as part of their use. Thus in turn naturally drives growth. No wonder we’re creative AI tools spreading rapidly based on people posting the amazing creations — whether it’s 3D assets, video snippets, or gorgeous images — on all the highly visual social networks. As we jump from one S-curve (mobile) to the next (AI), we are seeing the novelty drive come back into the ecosystem. People share and invite and discuss simply because they are excited about new product functionality — simply because of its “it actually works” feature.

Instead of highly optimized flows that have been endlessly A/B tested, startups can simply show a first gen AI tool for making okay-but-not-great videos, and everyone will endlessly talk about it. One day this novelty will settle down, but until then, game on!

I think we’ll also see, with smarter AI-powered conversations, that marketing will look more like sales over time. Rather than 1:many broadcast, we will have many 1:1 agents selling people over chat/phone/video and providing a truly personalized pitch. We only have marketing because 1:1 sales for everything is too expensive. But with AI allowing people to convert $ to labor, we will see unique combinations of mass 1:1 sales with brand efforts to give your virtual salesforce air cover. And along with sales, mass personalized landing pages, product experiences, and so on. Everything will be white glove and concierge, rather than mass-produced.

Excited to check in again in 10 years!

this was an interesting point:

"I think we’ll also see, with smarter AI-powered conversations, that marketing will look more like sales over time. Rather than 1:many broadcast, we will have many 1:1 agents selling people over chat/phone/video and providing a truly personalized pitch. We only have marketing because 1:1 sales for everything is too expensive. "

I actually feel the opposite, that sales will look more like marketing. We only have sales because marketing is so non-personalized.

But maybe its semantics at that point.

Perfect insights as always 🔥