The case against morning yoga, daily routines, and endless meetings

How to maximize 10x work and avoid thoughtless daily 1x work routines

Do androids dream of executing routines?

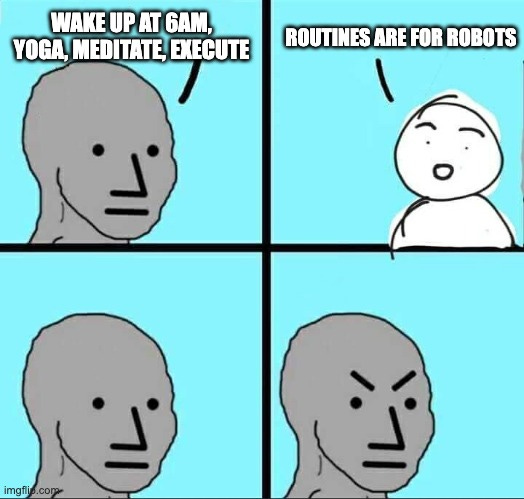

We are stuck in a world of routines: Wake up, answer email, go to a meeting, then another meeting, check off an item from a todo list, and repeat. The “hustle culture” of the internet tell us to add even more to the routine: Grind more hours, wake up at 5am and do yoga, remember to meditate, work out an hour a day, and so on. There’s endless tips on what successful CEOs do with their mornings, making us feel bad for not executing core loops with machine-like efficiency.

You’ll get none of these ideas here. This is the anti-routine essay, in which I refute the paradigm of fitter, happier, more productive routines as the secret to success. Our careers are defined by the highest moments of its biggest upside swings. The question is how to create the most opportunities at achieving that, not how to execute perfect little habits. That is: Reject the core loop, the checklists, and all the email. Embrace serendipity!

10x work

Imagine the thousands of tasks you did in the past year and sort them by impact. How many of them actually moved the needle? I’m certain this list of tasks would sort themselves into a power law where a tiny number of high upside tasks drove the most impact. These are what I’ll call “10x work” — these are key tasks where your doing them well/poorly really matters, and the result might define your professional output for an entire year (or more).

10x work is weird and often the opposite of routine. 10x work seems to come up randomly, often hang on a few quick and important decisions, unfold in a few days or weeks, and the results can be huge (or catastrophic). Often there’s no undo button. A deal might fall apart and never recover. A product launch might cause usage to explode, when the right punchline in the launch video is crafted. 100 lines of brilliantly written code might be the difference between state of the art versus rapid obsolescence.

Some additional observations:

Within this framework, daily routines are often 1x work or even 0.5x work. Steady routines are comfortable but add no new information, and contain no risk, and no quantity of them will add up to 10x work.

The difference between a grinder and a lazy person is only 3x — a grinder might work 100 hours/week versus a mere 30 hours for an oaf. Yet we routinely see people who are 100x or 1000x more productive than others. How?

People are often focused on the defensive practices to free up more time — canceling 1:1s, blocking off time, “no meeting Thursdays.” These are necessary but not sufficient. The question is, how do you decide what to prioritize in this free time? How do you pick tasks that will have true upside, not just defend our calendars better?

The most conscientious among us are great at setting goals, keeping track of progress, and crossing off items on a checklist. And that’s great, but often this just creates stronger adherence to a routine. I ask, how do you best decide what’s on the list? How do you ignore the >50% of tasks that don’t actually matter?

Don’t get me wrong — of course I’m all for removing the long and unproductive tail of the power law. You should learn to say no to more stuff, cancel the bottom 20% of your meetings, crush your checklists, and answer emails in windows. Throw in some meditation too. I’m just arguing, that’s not enough!

Breaking routine

The problem with 10x work is that it’s often unclear it’s happening until it happens. You often don’t know that a moment is important until you connect the lines after the fact, because it might be a chance idea that spawns a new project that then reinvents the company. It’s why we often read about accidental inventions, or huge technology waves that start as hobbies. However, I’m convinced that you can create an environment where 10x work is more likely to come up. That’s because at its core, 10x work thrives on agency, serendipity, and new information:

10x work happens at the frontier of knowledge, away from the routine. It’s where no one knows anything. In my industry, in tech, the technology frontier often has hype, excitement, and opportunity, but not enough people to do the work. The status hierarchy hasn’t been set, nothing’s been written down, and it’s unclear to anyone what will work. As a result, it’s an equalizing force. Today, this is web3, VR, gaming, AI apps, deep tech, longevity, etc, but tomorrow it will be something else.

Pivotal moments often happen when you inject more risk, new information, or create upside in an otherwise stable situation. This is why people talk about a sequence of key events precipitated by changing new jobs, meeting a new mentor, launching products, moving across the country, etc. These are moments of great change, and thus, tremendous amounts of new information. Start new projects and make big moves. Raise your hand to volunteer for work with high variance outcomes.

Execute based on your own plan and not in reaction to others. Agency and ownership rule the day, and this is why “Send email to X” is stronger than “Send reply to Y” — the best work does not happen in reaction to what others do. Just build your own plan based on your goals and the information you have at hand, and don’t be afraid to update it as you get market feedback. In the same way, it’s important not to get caught into the loop of simply doing work that is assigned to you, answering emails that are waiting in your inbox, etc. Reactive loops are easy, but lead to decay.

Serendipity loves randomness and hates routine. This is why I’m so positive on sending outbound emails to interesting people, hosting dinners and events that bring together smart folks, and publishing any and all thoughts online. There’s often followup, and opportunities present themselves randomly. I’m also pro reading random books on a topic, or googling/wikipedia’ing/chatGPTing for hours to dig into things — sometimes semi-random exploration leads to the best ideas. (On the other hand, I’m usually negative on low-signal socializing at conferences and random coffee 1:1s that don’t move things forward. These are fun but are too low yield)

Find leverage. Create work assets that compound over time so that it spreads even when you sleep. Maybe this is a project you’ve put out into the world, and customers can find it and share it. Or it’s a series of videos or essays that grow in audience over time, and each new bit content builds upon the last. Or build a decentralized conference, as we’ve recently done with “Tech Week” that causes a spontaneous community to form, with scale and energy. This type of work grows non-linearly, creating surface area and increasing serendipity. This is why I’ve become a fan of “building in public” rather than creating a ton of decks/memos/etc but then hoarding them for internal/private use online. This is also why I’m a fan of bringing networks together with events, content, and investment.

Sign up for the “tests of skill.” You can learn all that you want, network with great people, and never know if you have what it takes. Sign up for the projects that can have a real chance of success or failure, and where you can be responsible for the outcome. Within bigger companies, these are the new/unproven projects, or just join a startup. These are the big pivotal moves that force you to learn as fast as possible.

Find time to invest in your comparative advantage, because it’s another non-linear asset to compound over time. It’s not enough to just be competent at what you do — learn its history, and figure out where it’s going next. Teach, critique, and discuss. Explore and define the next frontier. Become the best at the one specific thing, or top 25% at two or more things.**

On this last point, I’ve stolen this from Scott Adams (of Dilbert fame) who talks about the idea of comparative advantage in this passage which I think is worth mentioning.

Adams gives a good hint on how to ultimately pick a goal within a larger master plan. This process of orientation creates a context to all the potential projects/work/networks that you can do/build.

Scott Adams writes:

If you want an average successful life, it doesn’t take much planning. Just stay out of trouble, go to school, and apply for jobs you might like. But if you want something extraordinary, you have two paths:

1. Become the best at one specific thing.

2. Become very good (top 25%) at two or more things.

The first strategy is difficult to the point of near impossibility. Few people will ever play in the NBA or make a platinum album. I don’t recommend anyone even try.

The second strategy is fairly easy. Everyone has at least a few areas in which they could be in the top 25% with some effort. In my case, I can draw better than most people, but I’m hardly an artist. And I’m not any funnier than the average standup comedian who never makes it big, but I’m funnier than most people. The magic is that few people can draw well and write jokes. It’s the combination of the two that makes what I do so rare. And when you add in my business background, suddenly I had a topic that few cartoonists could hope to understand without living it.

Capitalism rewards things that are both rare and valuable. You make yourself rare by combining two or more “pretty goods” until no one else has your mix…

It sounds like generic advice, but you’d be hard pressed to find any successful person who didn’t have about three skills in the top 25%.

Naval later added to this idea:

Let’s say there’s 10,000 areas that are valuable to the human race today in terms of knowledge to have, and the number one in those 10,000 slots is taken.

Someone else is likely to be the number one in each of those 10,000, unless you happen to be one of the 10,000 most obsessed people in the world that at a given thing.

But when you start combining, well, number 3,728 with top-notch sales skills and really good writing skills and someone who understands accounting and finance really well, when the need for that intersection arrives, you’ve expanded enough from 10,000 through combinatorics to millions or tens of millions. So, it just becomes much less competitive.

Also, there’s diminishing returns. So, it’s much easier to be top 5 percentile at three or four things than it is to be literally the number one at something.

The way I interpret this, in the context of 10x work, is that you want to be pushing in the direction of experience, learnings, professional networking, etc that align with becoming #1 at something, or top 25% of multiple things.

If you have the self-awareness to figure that out, and iterate as you learn, then all the other techniques of creating serendipity and accumulative output gets you climbing that the power law curve of productivity. Contrast this to 1x work that happens within repetitive routines — they might put you in a holding pattern where you make incremental progress around these sorts of goals, but you’re not proactively moving towards #1 or top 25%.

The 10x plan for 10x work for 10x people

Let’s go back to the power law, where I initially complained was full of long-tail 1x work.

What would we like the curve to look like instead?

For the long tail — remove/delegate/automate the <1x work. If it doesn’t matter much if it’s done well or not, then just get it done. There’s so much written about this that I won’t dive into it much here. This is the “playing defense” part.

For the 2-5x work, keep doing it — it is “work” after all. But perhaps figure out how to align it towards your plan for work and life?

For the head of the curve — we need to remind ourselves that our careers are defined by the highest moments of the biggest swings. Let’s maximize these opportunities. Make a Master Plan, and then pick a direction and go! Embrace more serendipity, talk to more interesting people, take more swings, and go deep on your craft. Proactively position yourself to jump into action when 10x moments emerge, and create the opportunity to pour resources (time, people, capital) into a project that catches on.

You’ll note that there’s no yoga or meditation on this list. (But fine, do it if it helps). And I don’t advocate working even more hours. In the end, I’m not sure that it’s possible to avoid the ~60 hours/week we all spend on emails/meetings/etc., and the most productive people on the planet aren’t working that much more than that. Perhaps someone like Elon can breathe/sleep his work and increase it +50% more, but not 3x or 5x. It’s just not possible. To achieve more, it’s more about how you fill the time you have.

By its nature, the opportunities for 10x work are not really something you can optimize. Sometimes it’s a random work idea, or a random meeting, or a off-hand tweet (like my “growth hacker is the new vp marketing” tweet from 10 years ago) that creates a lucky break. Combine this with skills built up with years at the technology frontier, and skill and serendipity can come together. As comedian Steve Martin says, “Be so good they can't ignore you.”

Reject the core loop, the checklists, and all the email. Embrace serendipity!

Generally agree with this, but the perspective I would add is: a good routine *makes space* for the 10x work, in part by taking care of the less important decisions ahead of time.

“Be regular and orderly in your life, that you may be violent and original in your work.” –Gustave Flaubert

One of the best blog posts I've read. I suspect I might back in a few years and think "that was a profound moment in my life."

Some thoughts:

- I think there's a case of this, among more successful people, where 10x work in the past that paid off leads to 1x work now. Responding to email is a good example of this.

- Personally, routines have been most effective in domains where the upside is capped (like brushing my teeth or exercising) and least effective where the upside is uncapped (like at work).