Time sinks and money sinks

How business models drive product design and user behavior

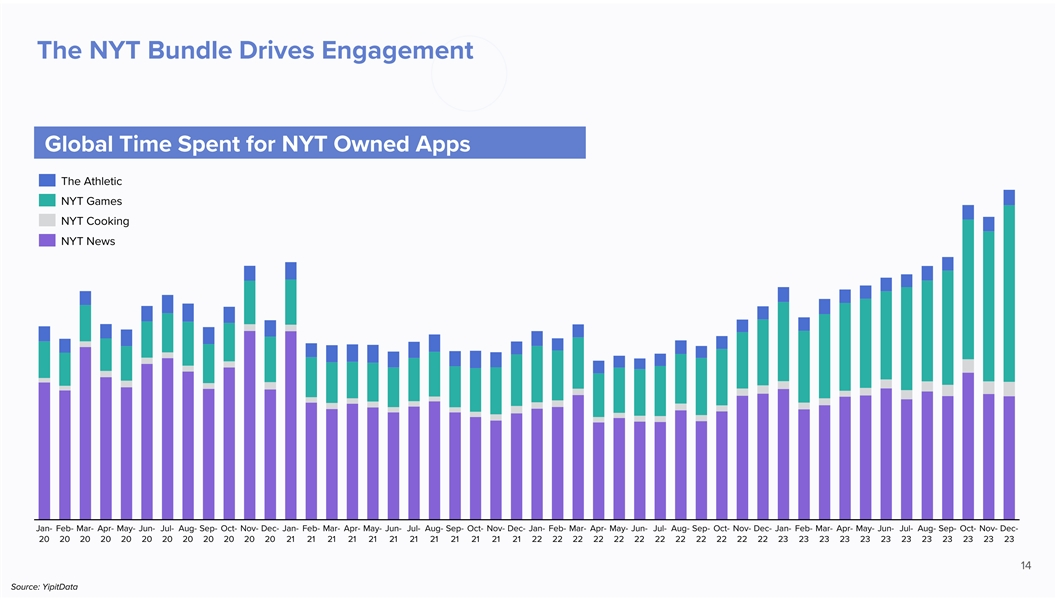

The New York Times is now mostly a games company — just look at this chart.

This trend is noticeably accelerating in recent years. While their news division might continue to be culturally relevant, we may end up thinking of it as the bookstore part of Amazon — it exists, but is not meaningful to understanding the NYT. Today the NYT pushes you towards one subscription bundle, which they call “All Access” at $25/month, and you get news, cooking, sports, and gaming — and increasingly, people spend most of their time on NYT Games. It only makes sense to add more gaming to the bundle over time, and by the way, this is exactly what Netflix and Amazon are doing as well. More will follow suit in the future.

To dramatically oversimplify the internet, every product on the Internet is just one of two things:

Time sinks. High engagement, sticky, with endless scrolling/tapping. These apps live on the home screen. Usually free or free-ish, so they are terrible at making money when measured on a $/hour basis.

Money sinks. Low engagement, you are there to do a job, so you just need it to work. But at the end, you might pull out your credit card or fill out a form that generates a ton of $. These apps don’t live on the home screen — sometimes you only visit because you tap on an ad

The apps that fit into the bottom category (ecommerce, real estate, finance, etc) are often highly episodic and aren’t meant to retain users well. You’re in market for a car, then you make a buying decision, and then you have no need to ever visit a car comparison website again. Thus, they typically buy users from the top category (social networks, news, etc) since the time sinks are great at retaining people.

Thus, these products tend to specialize. Products that are great at being time sinks typically end up spending all their time trying to get as sticky as possible, and worry about monetizing later. Products that are great money sinks tend to focus on acquiring users profitably and pushing them through a conversion funnel towards eventual monetization. Or if you are a large, scaled tech company, you can maybe put both into a single bundle — Google owns email/search/browsers/etc but also has built out individual products for shopping, flights, etc.

Be careful with metrics benchmarks

I meet a lot of founders that — regardless of whether they are a time sink or a money sink — will use all the standard metrics, like DAUs or D1 or DAU/MAU or otherwise.

To give an example, a while back I did a roundup of the metrics I often look at to determine product/market fit — these are all pretty common things to look at:

cohort retention curves that flatten (stickiness)

actives/reg > 25% (validates TAM)

power user curve showing a smile -- with a big concentration of engaged users (you grow out from this strong core)

viral factor >0.5 (enough to amplify other channels)

dau/mau > 50% (it's part of a daily habit)

market-by-market (or logo-by-logo, if SaaS) comparison where denser/older networks have higher engagement over time (network effects)

D1/D7/D30 that exceeds 60/30/15 (daily frequency)

revenue or activity expansion on a *per user* basis over time -- indicates deeper engagement / habit formation

>60% organic acquisition with real scale (better to have zero CAC)

For subscription, >65% annual retention (paying users are sticking)

>4x annual growth rate across topline metrics

But are these metrics actually relevant to every business? No.

Unfortunately it can be easy to get dragged into memetic thinking, where you’re influenced both by conversations with other founders and investors who continually reference the same metrics. Because the loudest and most visible products, like say, Instagram, talk about DAUs, it’s easy to measure yourself by that as well. And when you install a standard metrics dashboard, they start by giving you the same readouts (active users! engagement length! etc) and that’s easy to fall into as well.

Products that are Money Sinks shouldn’t care about many of these metrics, and instead they should be focused on profitable acquisition of customers (thus, CAC/LTV and % organic acquisiton). And the conversion funnel from landing on the product into ultimately purchasing. The average order value. And the orders per month, and response rates from marketing. And a dozen other metrics that have a lot more to do with buying behavior than retention or engagement. Certainly products like this aren’t every day products, and if they are, the commercial intent probably isn’t there. (Search being the major exception to this idea, which is why it’s a gazillion dollar business)

I often give feedback on metrics dashboards with all of this in mind. You should pick your product strategy, then pick the metrics that validate that your strategy is working. You should avoid making product strategy decisions based on high-level metrics like DAUs because those are the metrics that everyone else uses, and they will steer you towards generic product strategy. You need strategy, and metrics, that are tailored to your product.

How business model affects product experience/design

It’s become fashionable in recent years to focus entirely on product experience and ignore business model, when in fact they are very intertwined. I often use an example of how video games have evolved to show this relationship:

arcade games: They were designed to eat quarters. Thus, they tended to be very difficult so that you could have relatively short gameplay sessions and turn over the clientele

At home consoles: You go to Best Buy and buy it once for $60. Thus, you expect to be able to play it for dozens or hundreds of hours, and anything less is unacceptable. The games also became much easier so you could make your way through the content

MMOs: You pay $X/month, via subscription. The goal is to get you to stay retained month to month, so you need to never run out of content. Thus, the games need to have endless quests, endless worlds, endless content. And multiplayer experiences also mean that you make friends in the game, and never leave

free-to-play: Pay nothing upfront, and focus on very broad casual markets. There’s easy first levels, but they become hard later on (you get “pinched” and forced to pay). Or another variation is to build a game like Fortnite that’s free to play with all of your friends, very accessible, and then sell cosmetics as a form of fashion/interactivity with other players

You’d call all of the above “gaming” but in fact they are really many successive generations of very different products that have been influenced by their underlying business models. Based on how monetization happens, not only does the average difficulty of the games change, but so does the emphasis on multiplayer, content depth, and so on.

The evolution of newspaper and media

I used a gaming example here, but of course a similar set of changes have shaken the news/media industry over time. To run through a brief history here, I can’t help myself but to start in the 1800s:

the printing press gets invented, and people start printing pamphlets and eventually news. They are limited run and ~weekly, targeting the wealthy, and there’s no ads — it’s purely subscription (6 cents per month)

the first “penny press” newspaper is released in 1830. They have ads, are sold cheaply per issue (1 cent!) and targeted at the lower/middle classes. Advertising demands reach, so newspapers become more local, sensationalistic, and mainstream. A lot of “yellow journalism” followed where folks just made up stories. Just go read about The New York Sun’s 'Great Moon Hoax' of 1835 which claimed aliens had been discovered on the moon, and was covered seriously as if it actually happened. Or the phrase, “if it bleeds it leads” dates back to the 1890s, because murders and other grisly news attracts readers

the so-called “Golden Age” of journalism in the mid-1900s was really one where the industry broke into a locally fragmented set of monopolies/duopolies. I grew up in Seattle with the Seattle PI and the Seattle Times, for instance, and there were strong network effects to maintaining that order. All the consumers in a town would subscribe because the content was targeted, and the delivery networks were set up. All the advertisers would only want to spend their money with the largest newspapers, and thus it was mutually reinforcing. Sensationalism (comparatively) declined done during this period because the monopolistic system of local papers no longer needed yellow journalism to sell papers — they already had locked up a large local audience

The internet of course screwed this all up.

The newspaper business was a classic time sink, even though it existed in the physical world — you read your paper every morning, and sections like world news, politics, and opinion drove daily engagement and stickiness. But then in the back of the paper, classifieds and ads were the mechanism where the time sink business could sell eyeballs to the money sink businesses that bought ads. Early in my career, I used to work at a startup that partnered with the WSJ/NYT/etc and you’d often see huge differences in rates across various sections. Politics/opinion/news drove all the traffic, but advertisers didn’t like much the idea of being next to a terrorist attack or something else. Instead they often wanted to advertise in the Finance section, or Travel, or otherwise — more brand safe, but a lot less traffic. But this all unbundled, of course.

With the internet, we saw this break down with pure-play money sinks like Craigslist and eBay and Amazon emerge with the help of network effects and Google, become sticky enough destinations unto themselves. Thus, newspapers (particularly local ones) became less frequently the starting place for the internet, and their monetization model of advertising declined majorly.

The inevitable rise of clickbait, driven by business model

You might have noticed that the mainstream news has evolved in how it covers news. There’s a common complaint that it’s become more clickbait driven and sensationalism has returned. There’s a chart from Tyler Cowan that shows the frequency of political terms over time, and you can see a distinct increase in recent years. This chart just tracks the frequency of how much certain words have appeared in the NYT between 1970 and 2022:

There are a lot of explanations for the spike of many of the politically charged terms, but I want to point out that the inevitable effect of business model:

historically newspapers were most sensationalistic in the 1800s when things were most competitive, and when they were most trying to grow circulation

the golden age of journalism coincided with when the newspaper business model was most stable (and most monopolistic)

in recent years, newspapers and broader print media are in a fight to the death transition to digital. There’s been many descriptions of new media companies tracking real-time performance of articles and writers, which would obviously incentivize clickbait, particularly at a time when online distribution is dependent on sharing/engagement. The more an article prompts people to reply, or share, the more it spreads.

going forward as subscription begins to dominate, I am hopeful this may have a calming effect on online discourse because you are no longer competing to drive the biggest clicks for the biggest story of the day. Instead, you have a steady stream of revenue that comes in, buoyed by adjacent categories (games included), and writers will create the content their steady users want. (The counterpoint, of course, is that only the most hardcore customers subscribe — so do you just cater towards the top 1% more engaged people?)

Zoom out further, and we’re now seeing an evolution towards subscription bundles as the predominant business model for media beyond news — now you can include music, movies, gaming etc. This business model is of course super compelling because it allows the time sink products to monetize at higher LTV, and to sort of act like money sinks unto themselves. If you are large enough to start a successful subscription service, you can then layer on vertical categories like gaming, sports, cooking, etc. And if you are Netflix, Apple, Spotify, and Amazon, you start with video but then add podcasting, music, audiobooks, and eventually gaming as well. It could be that all of these media companies — regardless of their initial entry category — will end up being offering roughly the same media package.

But funny enough, they might all end up becoming gaming companies.

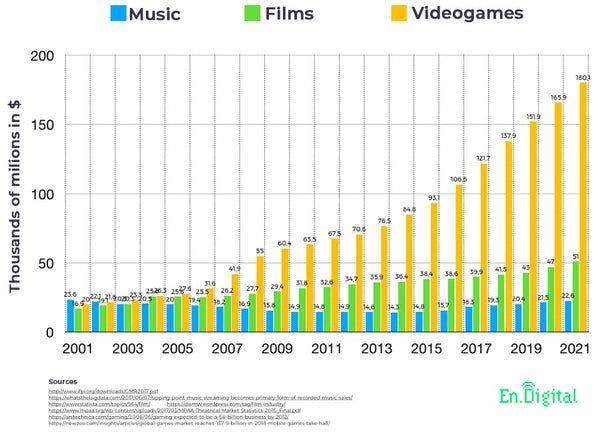

I leave you with two final charts to make that argument. First, the size of the video games market versus music and film. You could easily overlay news, TV, etc and it would all look the same:

And second there are tremendous demographic changes happening. Younger demographics play games, and aren’t watching TV. I think pretty obvious that this trend will only continue over time.

The NYT may be the first newspaper to become a gaming company, but it won’t be the only one — I assure you!

It seems these trends also showcase a significant shift from learning to entertaining as my overly simplistic generalization is that most games are consuming attention without teaching and improving people's lives. I for one am searching for examples of how gaming is improving society at large?

Another great article. I wonder if there’s a Substack model that could follow something similar: normal newsletters are free but you add something gamified behind a paywall.